Mutualism

Symbiosis is a term most people have heard and probably get the gist of it. But it's rather complex, as are most things biological. There are three main categories of symbiosis: parasitism, commensalism, and mutualism. The basis for the three categories lays in outcomes for the members of the species involved in the interactions. For parasitism one species benefits, while the other species is harmed. For commensalism, one species benefits, the other is neither harmed nor helped. And then for mutualism, both species benefit from the interaction. Mutualism sounds nice, let's investigate it a little further...

It's a win-win, but not so much for biological control - here are the players in one such mutualistic interaction:

All the players above have been introduced either accidentally or on purpose to California. Although they didn't evolve in California, there are conditions that have allowed for their establishment and survival; basically, where there is irrigation water. So in a typical situation we've got a hedge of holly growing in a landscape. It's a hardy plant and does well with its occasional watering. From a distance you wouldn't notice much insect activity, the plants typically look quite healthy. But upon closer inspection you'll notice something encrusting the lower branches and leaves, this is Chinese wax scale. You see the star-like nymphs on leaves (center left) and adults on stems and branches (center right). This insect doesn't look much like an insect, but the two most important features are there - a way to eat and a way to reproduce.

|

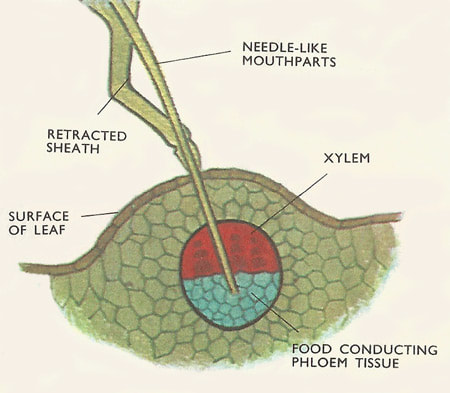

It's the eating part that is key to the concept of mutualism in this scenario. Scale insects are hemipterans in the Suborder Sternorrhyncha. A major feature of this group is that their mouthparts are needle-like stylets that are used to pierce into plants and suck out sap; analogous to how a mosquito feeds on a vertebrate's blood. But the Chinese wax scale mouthparts are concealed, so to illustrate how they feed we can look at the scale's relative the aphid. At the right is a side view of an aphid feeding on a plant - what the photo doesn't show is the thin stylets that are inserted into the plant through which the sap is sucked up into their mouth. The colorized scanning electron micrograph below gives you a glimpse of the stylets of an aphid in the act of feeding.

|

When the aphids or scale insects feed, their stylets are threaded into the plant and tap into the vascular bundle (see below) eventually finding a tube carrying phloem (=plant sap).

|

|

The phloem sap is a rich resource full of sugars, amino acids, and a whole host of other nutrients. And there is a lot of it. The tiny insects draw in the sap constantly, but they have a digestive system that filters out just what they need and shunts the remainder out of the body as a very sugary, nutritious excrement called "honeydew." Lovely.

Again, we look to our friend the aphid (photo to the left) to get a better look at the honeydew that is excreted, and just how much comes out every 30 seconds or so.

|

Honeydew production is non-stop and can accumulate on the plant's surfaces around scale colonies causing its own kind of sticky mess (photo below left). But quite often, the honeydew never gets a chance to accumulate because there are sugar loving ants prowling around. The Argentine ants are a prime example, scurrying around the scale colonies at a frenetic pace and sucking up the honeydew from the scales as it is being expelled (much like the ant in the image above taking in honeydew from an aphid). The ants take the honeydew into their crop, a food storage sack in their digestive system, and that enables them to fill up and return to the nest where they regurgitate the honeydew for its nest mates and the developing ant larvae to feed on. I never said bug biology was pretty.

So, we have a scenario of interactions here that includes plants, scales and ants. Plants make their own food, sap; scales eat the sap to make more scales and excrete the leftovers as honeydew; and the ants eat the honeydew to make more ants. This seems very mutually beneficial, but it's still a little too one sided, a little too linear. Nature typically likes cycles. So for this to be mutualism, rather than commensalism, we need to see that one of these players gets a reward, and it's the scales. In their interaction together, the ants and scales have a good thing going with the food exchange, but with the ants around all the time, the scales also get the benefit of their protection. Ants are highly protective of their honeydew-producing scale colonies, to the point where they will fight off or kill any potential scale predator they can find. The ants will even take scale nymphs gently in their mandibles and move them to other healthier parts of the plant or to other plants, thus giving them a chance to start a new robust colony and keep the honeydew flowing. That is mutualism, where both species get a benefit from the interaction.