Aphids & Parasitoids & Hyperparasitoids

Basic Aphid Activities

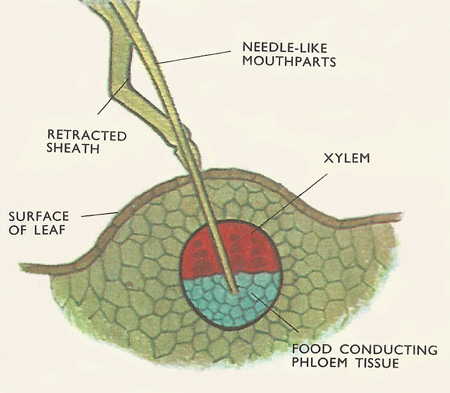

Feeding

Feeding on phloem - with piercing/sucking mouthparts. Needle like mouthparts are a hallmark of this group of insects and with them they tap into the vascular bundles in plant tissues - leaves, stems, etc. - and suck out the nutrient-rich plant sap (=phloem). The image below details the act of feeding in piercing/sucking insects, the diagram attempts to show what's happening microscopically.

|

Birthing

Giving Birth - aphids are adept practitioners of reproduction. Aphids have a complicated life cycle and make use of a couple of reproductive strategies to ensure a continual maximum offspring output per population. What is pictured above is a wingless adult female giving birth to a daughter nymph - which she can do up to 6 times per day (note she continues to feed during the process). She also reproduces without having had sex - no males in these populations.

In the diagram above, Geoff Brightling has illustrated the continuous process of offspring development inside the aphid mother.

|

Dispersing

Organismal dispersal - in response to environmental pressures or cues. Aphids do not excel in site fidelity. In a given population, some aphids will develop wings and fly away to find new resources to exploit in response to a decline in resource quality or changing environmental cues such as day length, temperature, etc. These dispersers are winged females that give birth to wingless females once they arrive at a suitable host plant.

Even a woolly apple aphid, heavily laden with waxes, is able to fly from one tree to the next.

|

Okay, now for the weirdness: parasitoids and hyperparasitoids

|

THIS is one of the most remarkable photos of aphid biology imaginable. My gratitude to Naomi Smith for taking the time to photograph it and having the intuitive know-how that this was indeed something special. Let me explain...

|

...what is pictured above is mind blowing enough as it is, but it's just the beginning of the story that leads to Naomi's gorgeous photo on the left...the insect on the right, above, is a parasitoid. A parasitoid, in this case a wasp, is an insect that reproduces by injecting its eggs into another insect. When the wasp egg hatches, the wasp grub or larva, feeds on the insides of the aphid as its only food source as it completes its growth through to adulthood.

|

The female parasitoid wasp on the left has detected a healthy aphid. There are a series of sensory cues emanating from both the plant and the aphid that help the wasp home in on her target. This type of wasp specializes in parasitizing aphids; no other kind of insect will do. These wasps have the ability to flex their abdomen forward, it's advantageous for her to keep her eyes on her target. The image on the right shows her holding her abdomen in the typical position as she inspects some aphids that may serve as potential hosts for her offspring. At the tip of her abdomen is an egg laying tube called an ovipositor. It typically remains hidden, but is extendable. Once she's ready to parasitize the aphid, her abdomen flexes forward, the tip contacts the aphid, the ovipositor - acting just like a hypodermic needle - pokes through the aphid integument and injects a single egg in less than a second. Once done the wasp continues her search for aphid hosts, injecting dozens over her lifetime of a few short weeks. Because these wasps inject healthy aphids with an egg, they are referred to as primary parasitoids.

How to make a wasp from an aphid...

The wasp egg inside of the aphid may sit quiet for awhile, often times to allow the aphid to continue to grow to full size. Again, this is the only food source for the developing wasp larva and if it doesn't get enough to eat, it won't survive. The images above show aphids with wasp larvae developing inside of them. At first the wasp larva feeds on non-essential innards, and the aphid remains alive. But then later on the wasp larva is growing rapidly and begins to feed more thoroughly. Eventually the contents of the aphid's body will be completely consumed. But before that happens, there's a twist...its called mummification.

The images above show what is referred to as an aphid "mummy". This physical change to the aphid's integument is remarkable in that it is directed by the developing wasp larva within. The reason to enact this change is straightforward. The wasp larva is feeding somewhat protected inside the aphid, but aphids are very soft and have lots of predators - therefore it's risky to be inside one. Also, once the aphid has perished, it's vulnerable to dislodging and falling to the ground where it's likely to be eaten, thus killing the wasp larva inside. These are not good outcomes for the wasp larva, so it converts its soft vulnerable aphid host into a hardened, stable container within which the wasp larva can more safely finish developing. The wasp larva starts this conversion before completely consuming the aphid by secreting chemicals from its body that hijacks the aphid's own cells and coaxes them into a transformation. First, the aphid body swells, then the underside of the aphid body becomes gel like, and that serves to glue the aphid down onto the plant surface. It is now secured for the remainder of the wasp's development. The final step in aphid mummification is for the remainder of the aphid integument to thicken and harden. Now the wasp has a secure home within which it can finish eating the rest of the aphid and go through its pupal stage.

|

Parasitoid wasps will work at parasitizing as many aphids as they can in an aphid colony. The image to the right shows varying stages of mummy development in one such colony. With luck, each mummy will eventually produce an adult parasitoid wasp who will then go on to parasitize more aphids. Below is a job well done.

|

Getting the wasp out...

In the image just above, you may have noticed some of the mummies have holes in them. Those are called exit holes and it is where the adult wasp cut itself an escape hatch and entered the world after having fed and pupated inside its aphid host.

|

Above a parasitoid wasp adult is slowly cutting its way out of the mummy using its mandibles. It has shed its own pupal skin while in the mummy and is ready to see the world. Below is an adult wasp emerging from the aphid mummy. The wasp life cycle is now complete. There was enough aphid to make just one wasp.

|

Here is a close up of the exit hole. Most primary parasitoids cut the exit hole with their mandibles near the center rear of the mummy.

The Final Twist...

|

This image shows the exit hole of an aphid mummy, but inside there is a cluster of small dark tapered objects. This is referred to as meconium. It is the waste from the wasp larva that was deposited as it was pupating. Another challenge for the wasp larva to overcome is not contaminating its only food source while it's feeding and growing. To accomplish that, the larva holds all of its food wastes in its gut and stores its metabolic wastes in another part of its gut. At pupation, the larva no longer needs to feed, the aphid is mummified and so its okay to finally evacuate all of those stored wastes.

|

|

There is a subtle difference on this aphid mummy that we talked about above. The exit hole is offset, it's near the head and off to the side a bit. Did something go wrong with the primary parasitoid? Did it get turned around? No. What happened here is far more interesting than that.

|

|

The wasp to the left has discovered an aphid and is injecting an egg into it, much like what was described above, but this aphid already has a primary parasitoid living and feeding inside of it. The wasp at left is called a hyperparasitoid and it isn't interested in having its offspring feed on the aphid, but rather the wasp larva already living inside the aphid. After she injects her egg into the parasitized aphid, her offspring will wait and allow the primary parasitoid wasp larva to finish feeding and growing and transforming the aphid into a mummy. Eventually, the primary parasitoid larva will eliminate its meconium and pupate. At that time, the hyperparasitoid larva that has been waiting patiently in the dark recesses of the aphid now begins to feed on the primary wasp pupa. The hyperparasitoid holds its wastes in the same manner as the primary because this is also its only source of food. Eventually, the hyperparasitoid finishes off the primary pupa, then pupates itself and eventually emerges as an adult, but for some reason chews its exit hole off to the side. And inside the mummy will be two deposits of meconium one from the primary and one from the hyper; one more bit of evidence of real biological warfare raging all around us.

|

So when you see a photo of an aphid mummy with an off-kilter exit hole, there's a very complicated story with intricate biological interactions required to explain it.