Biological Control History

For anyone trying to understand biological control, the typical starting point is the cottony cushion scale story. Biological control of the cottony cushion scale, Icerya purchasi, by the Vedalia beetle in 1889 in California is the basic starting point for the history of biological control, and according to Paul DeBach in his textbook, Biological Control by Natural Enemies, “…established the biological control method like a shot heard around the world.” The epic struggle between these two is illustrated in the image above.

The method, the real crux of the idea here is, moving a natural enemy population to reconnect it with its prey populations.

The method, the real crux of the idea here is, moving a natural enemy population to reconnect it with its prey populations.

|

Like any good story, it goes like this…

The set up: Some small group of plant-eating insects gets moved accidentally into a new area where they have never occurred before. That creates a situation where the group of insects may be able to establish if conditions are right. And indeed, somehow cottony cushion scales got moved from their native home in southern Australia into northern California in the 1860s, most likely on some infested plant material being shipped into the state. The scale population did establish and proliferate in the Bay Area and eventually spread all the way into southern California. |

The infestations of cottony cushion scale were so intense that citrus trees were literally covered with scale, making them look like they had been flocked for Christmas. Fruit production plummeted and many trees died.

|

|

The problem, part 1: Not all successfully invading plant-eating species turn out bad, but some do. To end up bad, the conditions have to be just right: there needs to be the right climate, the right food, the ability to reproduce, and the ability to spread. There also has to be at least one thing missing – mortality. Or at least some mortality has to be missing and that usually means some population regulating factor like a predator or other natural enemy. Take away that mortality pressure from a predator and all of a sudden you have many more offspring surviving than normal and that is when populations start to explode.

Turns out Australia and California share many similar climates. Cottony cushion scales feed on plant sap by inserting its needle like mouthparts into the stems and branches of many kinds of trees and shrubs. They also produce hundreds of offspring per female and disperse easily from one tree to the next. And without any natural enemies, their populations exploded throughout California. |

Above is a female cottony cushion scale. The white wax has been partially opened to reveal hundreds of her eggs and newly hatched offspring. The power of their reproductive potential is unleashed without some type of predator around to feed on the new generation.

|

|

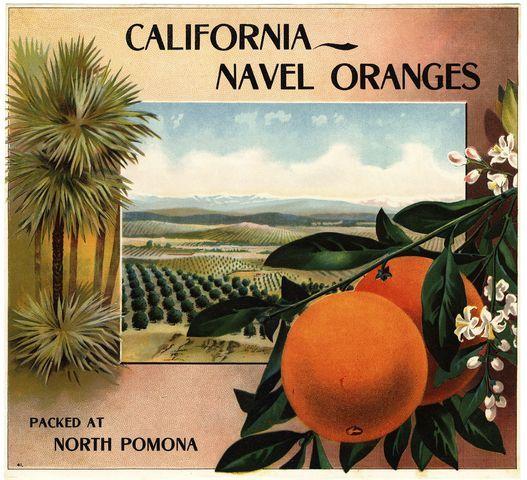

The problem, part 2: Cottony cushion scales thrive on citrus trees, and that’s a problem.

Citrus and “the idea” of California are inextricably linked. Citrus was a huge player in the early development of California’s economy and its marketing – it is called the Golden State due in part to the color of citrus fruit. Commercial plantings of citrus started in southern California around the time of the Gold Rush and continued to expand exponentially. With the addition of the transcontinental railroad California’s golden bounty could be shipped to far off markets on the east coast delivering sunshine in the form of a navel orange to the huddled masses in big cities in the dead of winter. California’s golden image became well established...that is until the cottony cushion scale came along and brought the industry to its knees. |

|

The problem, part 3: Human's typical response to overwhelming numbers of pests that threaten our food supplies or livelihood is to nuke them, in a figurative sense.

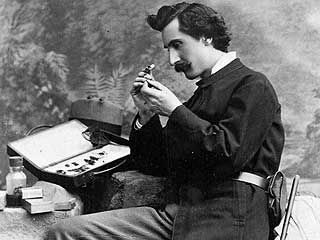

The cottony cushion scale overwhelmed the citrus trees that had been growing and thriving virtually pest-free for decades. Attempts to control the plague with arsenic, cyanide and other toxins was met with utter failure. The citrus growers let out a cry for help “…heard around the world.” And that cry did not fall on deaf ears. Enter Charles Valentine Riley, USDA Entomologist and first curator of the Smithsonian Insect Collection. This is the man who intended to move the natural enemy to reconnect it with its prey. He was a mover and a shaker, to be sure. The cottony cushion scale project wasn’t his first attempt at biological control. He had originally tried it by helping to move a predatory mite species from the US to France in 1874 in an attempt to control the invasive grape pest, phylloxera. Riley did not have high expectations for its success and he was right. But he did not give up on the idea. And so it was, when the citrus community in California called for help, he immediately began putting the pieces of the puzzle together to obtain predators of cottony cushion scale from Australia and liberate them into southern California. |

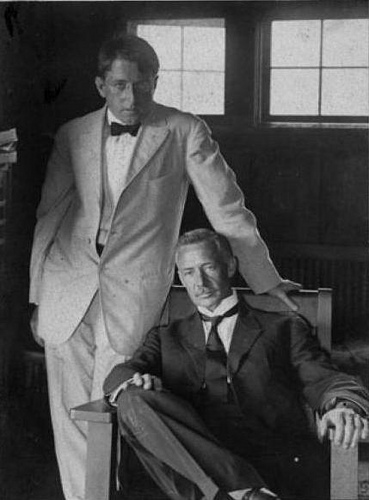

Charles Valentine Riley. Looking quite entomological in this portrait. You can read more about him here. Below is Albert Koebele, the eventual explorer credited with finding cottony cushion scale natural enemies.

|

The problem, part 4: Getting control of a newly invaded and exploding insect population by introducing its native, well-adapted, predators into the area of invasion. Is it even possible? Are we playing with fire by introducing an exotic species on purpose?

If Riley had any misgivings, they must have been put aside somehow because he had to do some interesting policy and political moves to arrange for an entomologist to get to Australia and manage shipments of live bugs back to California. Riley met with the California citrus growers in April 1887 and told them of his plan to send an entomologist to Australia to find the cottony cushion scale natural enemies. The growers were well-pleased and endorsed the plan, but provided no funds. To get the money Riley had to play a little shell game. Previously, the US government had put a stop to using federal monies to fund international travel for federal workers, done in large part to put a lid on Riley’s own travels to Europe for the phylloxera program. But in 1888, as luck would have it, there happened to be an International Exposition in Melbourne Australia and the US State Department was planning on sending a representative. Turns out the designated representative for the US State Department was an entomologist named Albert Koebele, arranged for by none other than Riley; sneaky. (You can read about the phylloxera program here)

If Riley had any misgivings, they must have been put aside somehow because he had to do some interesting policy and political moves to arrange for an entomologist to get to Australia and manage shipments of live bugs back to California. Riley met with the California citrus growers in April 1887 and told them of his plan to send an entomologist to Australia to find the cottony cushion scale natural enemies. The growers were well-pleased and endorsed the plan, but provided no funds. To get the money Riley had to play a little shell game. Previously, the US government had put a stop to using federal monies to fund international travel for federal workers, done in large part to put a lid on Riley’s own travels to Europe for the phylloxera program. But in 1888, as luck would have it, there happened to be an International Exposition in Melbourne Australia and the US State Department was planning on sending a representative. Turns out the designated representative for the US State Department was an entomologist named Albert Koebele, arranged for by none other than Riley; sneaky. (You can read about the phylloxera program here)

|

The Climax: Finding natural enemies to do the job, getting them back alive, and releasing them into the environment is the focal point of the biological control method.

As this project was getting organized, there was quite a bit of correspondence between the entomologists in California and Australia. In one exchange it was noted that there was a parasitoid fly species, Cryptochaetum iceryae, attacking cottony cushion scale in Adelaide. Shipments were made of the fly to California and they were released by a state horticulturist in San Mateo in 1888; even before Koebele left for Melbourne. Those flies established and spread throughout the cooler coastal regions of California providing substantial control of cottony cushion scale, that is still working to this day. But there were no records made and that release did not involve any of the cast of characters who eventually made biological control famous. When Koebele got to Australia he discovered the more famous predator, the Vedalia beetle, Rodolia cardinalis (pictured at right feeding on a scale). The beetle was feasting on cottony cushion scale and nothing else…a good sign. Koebele collected the beetles and sent three shipments back to California late in the year of 1888. Back then such travel was by steamship and the journey could take 3 to 4 weeks. So it was lucky that the beetles arrived alive, but 129 did and in January 1889 were liberated under a tent that had been set up over a cottony cushion scale infested tree in Los Angeles. |

The tiny fly above is called Cryptochaetum iceryae. It lays its eggs on a scale which eventually hatch into maggots and the maggots consume the scale's body. It's how parasitoids roll. This species may be the first successful movement of an insect as a biological control agent, but the event was never recorded.

|

The Denouement. How effective will the natural enemies be? Will they establish? Will they reduce the pest populations to levels that we can live with? Will they maintain those levels down the road?

By April 1889, the beetles had cleaned up the first tree with no ill effects and the tent was removed to allow the beetles to spread on their own throughout the orchard. The beetles proliferated and tens of thousands of them were eventually moved around orchards throughout southern California. Everywhere they went, they decimated the cottony cushion scale populations. It was a huge success and by the end of 1889 the cottony cushion scale was deemed no longer a threat to citrus production.

Shipments of fresh oranges from Los Angeles county to eastern markets jumped from 700 to 2,000 rail car loads in just one year. And what of the Vedalia beetles? It is not uncommon for people to assume that if the prey has been decimated that the predator left with nothing to feed on must then switch to feeding on something else. Not the case. Without prey, the predator populations naturally dropped. And then without the predator, the prey populations naturally increased. The key here is that the populations of predators and prey are intertwined and in the case of cottony cushion scale and Vedalia beetle in California, the populations never went extinct, but they did remain very low. Check out these interactions here. The scale populations remained so low that it was no longer considered a pest. That is what is meant by reconnecting the controlling factor. The natural, ecological roles have been reestablished and the problem solved.

And that may seem like a fairy tale ending to an exciting story, and it was for over a century, but then we got a little confused and momentarily wiped out the icon of biological control. To find out more - follow the link.

By April 1889, the beetles had cleaned up the first tree with no ill effects and the tent was removed to allow the beetles to spread on their own throughout the orchard. The beetles proliferated and tens of thousands of them were eventually moved around orchards throughout southern California. Everywhere they went, they decimated the cottony cushion scale populations. It was a huge success and by the end of 1889 the cottony cushion scale was deemed no longer a threat to citrus production.

Shipments of fresh oranges from Los Angeles county to eastern markets jumped from 700 to 2,000 rail car loads in just one year. And what of the Vedalia beetles? It is not uncommon for people to assume that if the prey has been decimated that the predator left with nothing to feed on must then switch to feeding on something else. Not the case. Without prey, the predator populations naturally dropped. And then without the predator, the prey populations naturally increased. The key here is that the populations of predators and prey are intertwined and in the case of cottony cushion scale and Vedalia beetle in California, the populations never went extinct, but they did remain very low. Check out these interactions here. The scale populations remained so low that it was no longer considered a pest. That is what is meant by reconnecting the controlling factor. The natural, ecological roles have been reestablished and the problem solved.

And that may seem like a fairy tale ending to an exciting story, and it was for over a century, but then we got a little confused and momentarily wiped out the icon of biological control. To find out more - follow the link.

A Bit More of Biological Control History

|

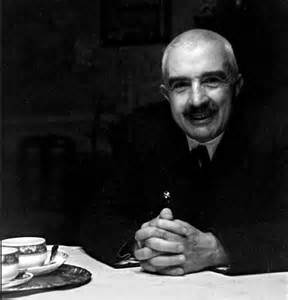

The affable man seated in the image to the right enjoying a cappuccino is Filippo Silvestri, a renown Italian entomologist. In 1910, he was hired by the Territory of Hawaii to travel to western Africa to search for and return promising natural enemies of the Mediterranean fruit fly for its control. In an address given at UC Berkeley in 1928 he offered the following advice to then current and future biological control explorers:

1. Know the native home of the injurious pests for which natural enemies are desired. This is often very difficult and complicated. 2. Visit as many localities as possible in which the pest is native. 3. Collect as much material, including all stages of the beneficial insects desired in these different localities, as is obtainable. 4. Collect the material over a long period of time, at least six or seven months or better a full year in order to secure as great a variety and quantity as is available. 5. From accurate observations and experiments, if possible, choose the most promising natural enemies available in the different localities. 6. Study the biology of the natural enemies and distinguish between primary and secondary parasites. 7. Eliminate all possibilities of introducing secondary parasites and other injurious insects. |

Introduction biological control is the primary method for introducing new natural enemy species into novel environments to aid in pest population regulation. The work is conducted by scientists associated with universities and federal and state government agricultural agencies like the USDA and California Department of Food and Agriculture (CDFA). Federally approved quarantine facilities are required to process the natural enemies before release into their new environment. The banner at the top shows cottony cushion scale, a formerly severe pest of citrus, being eaten by a Vedalia beetle adult. Vedalia beetle was the first major biological control success and took place in southern California in 1888-89.

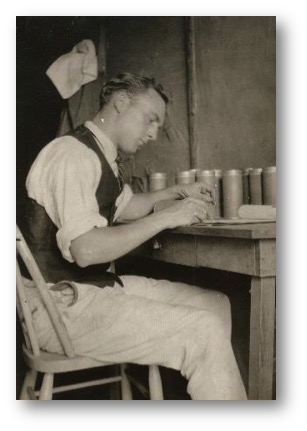

To the left is Harold Compere, one of biological control's greatest explorers pictured on his first trip to Australia in 1927 at the age of 31. 8. Study methods of transporting the beneficial insects and provide sufficient food en route.

9. Introduce as many parasites and predators as possible. 10. Expect to contract and endure diseases and hardships often with poor accommodations. 11. Work all of the time to take care of the beneficial insects collected. 12. Surmount every difficulty. 13. Have confidence in and a real love for the work. It is ironic to note that his travels in western Africa were misguided, as the original home of the Mediterranean fruit fly was later determined to be in the eastern Highlands of Kenya and Ethiopia. |

Some Other Interesting Foreign Exploring Stories

|

There are two interesting explorer studies in an obscure publication of the Brooklyn Botanic Garden Record's Plants & Gardens series titled "Handbook on Biological Control of Plant Pests" vol. 16, No. 3 published in 1960. PDFs of the two articles are below. One is about the journey of Dr. Fredrick Muir (seated below with Naturalist Joseph Rock) as he traveled in Borneo and Papua New Guinea in search of natural enemies of the cane borer, written by Richard Doutt. The second is a fascinating story of a woman's perspective on foreign exploration, with lessons that resonate to the present, by Irene D. Dobroscky.

|

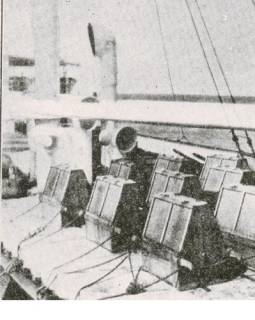

Below are some images that show the challenges of transporting natural enemies back to the US before intercontinental flight. Early on it was steam ships, but sometimes draft animals had to be used to transport plant material hosting the pest and its natural enemies to ports. The cages on the lorries below are called Wardian Cages and they house potted plants infested with the insects.

Once on the boat, the plants and their precious cargo had to be secured and cared for throughout the voyage, often for several weeks.

| ||||||||||||